Image source

“If ever there were a time to remember that professors are workers and that universities are workplaces, that time would be now. Administrators believe your job is worth dying for as they cynically use the bodies of employees to pad their bottom line.” Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Last fall, as part of her sabbatical, Anita had the chance to enroll in a course called “Working Class History” through the New Brookwood Labor College. The New Brookwood Labor College “strives to address racial, economic, and social imbalances of power by educating workers into their class.” During the first class, Anita and her classmates, most of whom were union members or union organizers, discussed what “working class” meant. They talked about how class definitions were not about how much income you earn, but about how you earn your income. It’s about workers who work for someone else. It’s about you creating profits for others. It’s about the exploitation of your labor, in the Marxist sense, and not just about how you are treated by your boss. A nice boss is still a boss.

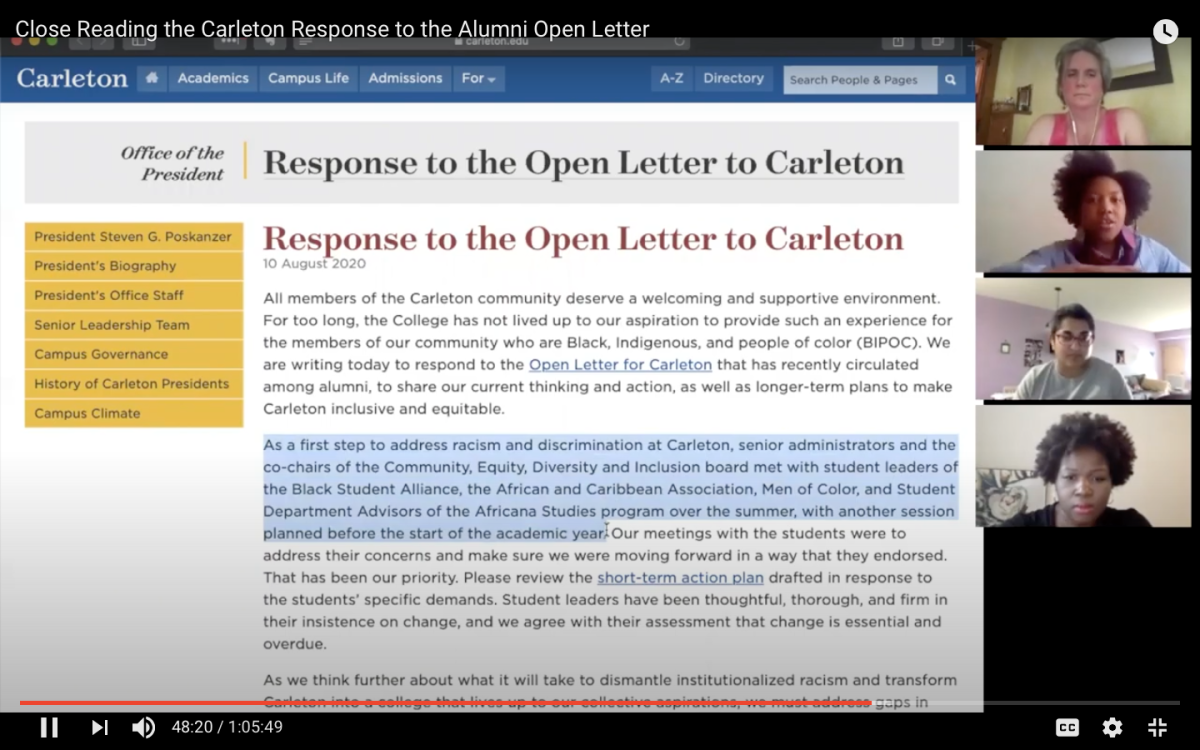

Anita thought about this first class discussion this summer as we entered a phase of the fall planning at Carleton where there seemed to be a lot of decisions being made that had implications for faculty and staff health and safety without the full participation of faculty and staff. While we are concerned about the staff at Carleton and their ability to prioritize their health and safety and still keep their jobs, we will focus in this post on faculty because we feel like we can speak from/to that position since we occupy it.

Recent conversations among the faculty about the fall planning process have included more direct discussions about faculty positionality as workers. While these discussions come out of particular frustrations about the process of decision-making this spring and summer about fall term planning, we were struck by how it was the first time the two of us have been part of discussions at the college where faculty members are identifying themselves explicitly as “workers” and administrators as “bosses.”

There’s definitely something about working at a private SLAC that insulates faculty from thinking of ourselves as workers. This post reflects our attempt to work through what these factors are. But first, as we thought about all the reasons for why faculty generally do not foreground their positionality as workers, we thought it might be useful to reflect briefly on what has influenced the two of us to see ourselves that way.

For Anita, a huge influence on her thinking about labor and economic justice was the fact that both of her parents were part of unions during their time living in New York City; her dad is still a member of the TWU Local 100, New York City’s public transit union and her mom was a member of District Council 37, New York City’s biggest public employee union. She remembers going to union rallies with her parents. While as a teenager she could not have articulated well why she thought collective organizing and bargaining was beneficial, she vaguely understood that, for example, she and her brother had access to a fuller range of healthcare benefits, including access to braces and glasses, because of her parents’ unions.

Adriana thinks she was probably influenced by her parents’ labor precarity in her 20s (both lost their jobs during the economic downturn in the early 1990s) and by her general attention to the structures of academia in the last ten years. In working through the way race matters in academia, she has read broadly in Critical University Studies, an area of inquiry that, in analyzing and critiquing the neoliberal turn of universities, stresses the importance of thinking about the condition of adjuncts and what that says about universities.

Our top six list of why faculty at a SLAC don’t easily think of themselves as workers

1.

Universities have large populations of adjuncts and grad students who face precarious work conditions in academia, and both groups have been doing incredible labor organizing in the past few years (see, for example, the COLA campaign at the UC schools). The situation is different at Carleton: as an undergraduate-only college, we have no grad students and we tend to have far fewer adjuncts than large research universities do. From her time on the committee that is concerned with faculty equity issues, Anita recalls a conversation with non-tenure track faculty with long-term contracts talking about how they were mostly satisfied with their labor conditions. In addition, as a private school, our salaries are not publicly available which makes it difficult to know about disparities in pay and benefits across ranks of faculty, let alone the differences between staff, faculty, and administrators. Comparisons with visibly unequal institutions that are more clearly exploiting their grad students and adjunct faculty helps to produce a sense that we work at a relatively equitable institution where we don’t need to advocate for ourselves.

2.

Small colleges in small communities tend to promote the idea that our participation in the lie life of the college makes us a family member rather than a worker.* There’s a certain level of “sociality” expected from faculty that often includes evening and weekend social events. We have had many discussions about the social demands of our jobs as professors, which includes both the relationship-building work that we see both as necessary in certain contexts and as unnecessary remnants of a bygone era where all the professors were married men who lived within walking distance of the college with wives did not work outside the home who welcomed students in their homes with elaborate home-cooked meals [or at least that’s what Anita was once told by an older alumnae in response to the fact that she did not live in Northfield].

The actual degree of sociality required to create learning environments that are humane and safe enough for students to take risks is debatable. But we see many colleagues (and ourselves, well, at least Adriana!) baking brownies to bring into classes, holding office hours in the evenings or weekends, hosting department events at our homes, inviting students over for dinner… And students are told and sold on the promise that being a student at an elite, small, liberal arts college means they get these kinds of relationships–family-like–with us. Faculty are not just purveyors of content expertise, but facilitators of individual growth and communal care and consideration.

Of course, this is all still labor. Just because this work is affective and relational does not make it leisure, or our “own.” But because it is affective work, both the institution and its workers can forget to “count it.” Care work is historically undervalued and unpaid in a capitalist society, and in our case, this kind of work can be viewed as personal and individual, rather than being a part of the structural conditions under which we labor.

*lie was a typo… or maybe a Freudian slip. We’ve corrected it but left the original so that both lie and life can live on here.

3.

Because we are a small workplace, there is a kind of personalization where we fail to see structures because we are thinking about the particular individuals who occupy the positions of hierarchy. The fact that we get to address the Dean of the College or the President by their first name hints at a particular kind of intimacy (going back to that “family” rhetoric) that often obscures the hierarchical structure of decision-making.

The personalization of the structure also means that we can mistake the moments where we are seen and helped as individuals as indications that labor conditions are good. What we mean is that personal relationships and their relative health can make us overlook structural problems, perhaps because we don’t experience a problem or because we trust that the particular individuals in positions of power are doing their best.

4.

Carleton has norms of departmental and faculty autonomy for curricular issues. What this means is that, even though there are pressures for pre-tenure faculty to conform to certain departmental and college norms, we do not generally have to get approval for our syllabi and pedagogical styles. Most recently, as the college delayed informing faculty about what our fall term would look like, faculty felt strongly that they should have autonomy to choose their mode of teaching (e.g online, in-person, hybrid). The administration has allowed faculty this autonomy.

This arena of autonomy can obscure or overshadow the moments when we have less input into decisions. We’ve both been in conversations where concerns about decision-making structures and processes get short circuited by the line “but at least we got to choose our teaching mode.” In other words, this particular area of autonomy and control can make us feel like we employ ourselves and we have choices and autonomy about our laboring conditions, even though there are many other decisions being made–not by faculty– that will impact our teaching contexts.

5.

Related to the promotion of our small, elite SLAC as a family, there is an incredible amount of messaging at Carleton about how “special” the college is. While we tend to think of this kind of marketing as being aimed at students, it is, of course, being consumed by faculty as well. And we get our own booster speeches at the top of every faculty meeting. We are told how especially dedicated and wonderful we are, how we are one of the “top” undergraduate teaching institutions, and how our work and dedication to our students and the college is much appreciated. Having colleagues in all kinds of institutions, including ones that have far fewer resources such as community colleges and tribal colleges, the two of us don’t really believe the hype. Are Carleton faculty dedicated? Yes, and so are all of our friends and colleagues who are teachers. But at Carleton, we also have access to an incredible level of human and materials resources.

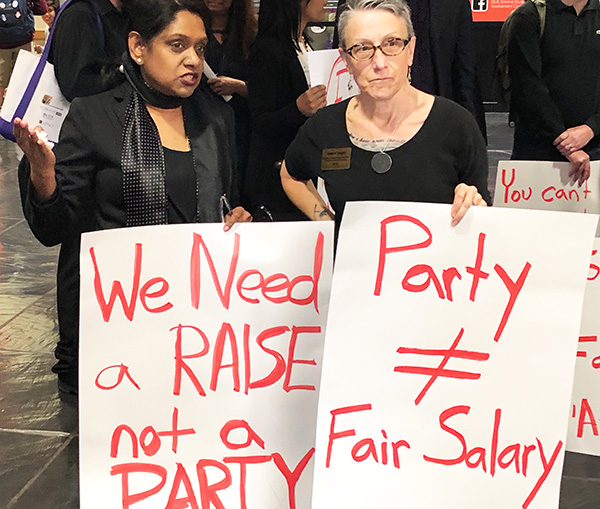

This pervasive discourse of how “special” Carleton elevates our labor to something remarkable and essential, which serves to slow or stall critiques of working conditions because “critique” is made to look interruptive, rude, or antagonistic. Within this framework, recognizing our labor and collective organizing to better our working conditions is an affront to the institution who values us and our specialness. Institutions demand loyalty and pretend to give “love and appreciation” as a way to obscure the fact that we are laborers, laboring for an institution with entrenched hierarchies of who holds decision-making power, especially over financial matters.

6.

Lastly, our own sense of our identities as being highly educated and credentialed can get in the way of seeing ourselves as workers. PhDs can feel like credentials that set us apart from other workers. For faculty who come from working class or lower middle class backgrounds, becoming a professor offered social mobility and stability. At a college like this, the PhD serves to make us “special workers” deserving of special benefits.

An example. Both of us remember how ten or so years ago the faculty had discussions about whether the “tuition benefit” (basically, certain college employees can get financial support from the college to pay for their children’s college tuition) should be expanded to all staff, including hourly paid staff. While many faculty spoke in support of the proposition, we can remember some faculty members talking about how their PhDs made them “nationally competitive” and therefore the tuition benefit would attract the “best faculty”–as opposed to thinking of the tuition benefit as a benefit that should be available to all children, regardless of how and how much their parents happened to get paid by the college. In the end, tuition benefits are still only accessible to faculty and certain groups of staff.

These differences in salary, benefits, and status, along with a governance structure that tends to silo faculty and staff interests and concerns (for example, while faculty have faculty meetings and a “Faculty Affairs Committee,” staff have their own informational structure) means that there are few spaces where we can focus on issues that we all might have in common as employees of the college. We both had conversations with our staff colleagues about how frustrating the fall planning process was because of the separate meetings for staff and faculty, as if we didn’t have common concerns about our health and safety and about the viability of the plan to bring back 85% of our students.

While the immediate concerns about the lack of faculty power in shaping the college’s fall plan has brought to the forefront our position as employees, like all other employees at Carleton and beyond, we hope that these concerns shift more fundamentally our sense of ourselves and our willingness to organize collectively as laborers, drawing inspiration from workers’ rights campaigns within and outside of academia.